When we reflect on our distant ancestors, we often picture them in a world devoid of modern amenities like toothbrushes and dental floss. However, it may come as a surprise that prehistoric humans actually had far fewer cavities than we do today. A recent study of teeth dating back 4,000 years reveals intriguing insights into why this was the case.

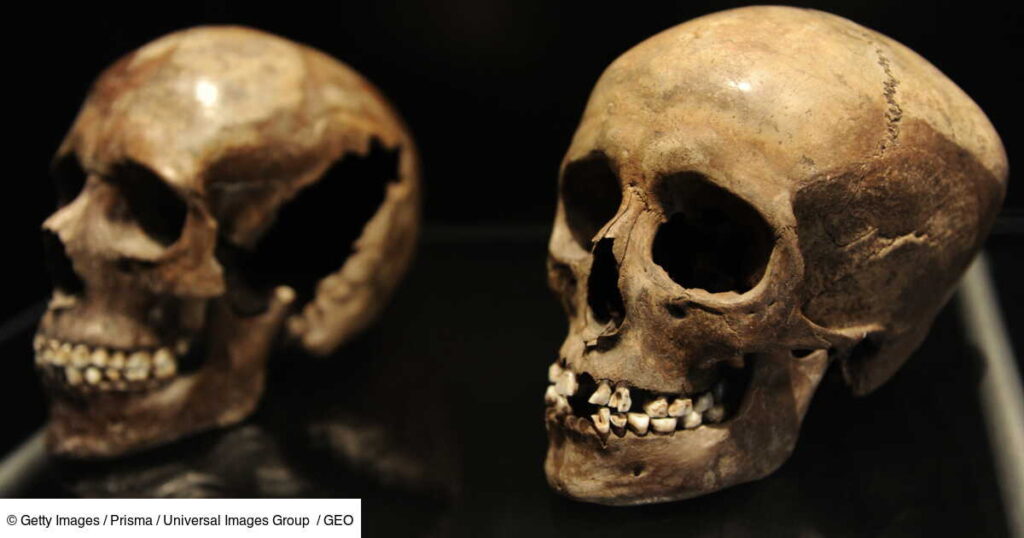

Unveiling 4,000-Year-Old Teeth

Recently, a team of archaeologists stumbled upon two ancient molars belonging to a man from the Bronze Age, specifically between 2280 and 2140 BCE, located in a limestone cave in County Limerick, Ireland. What they discovered within these teeth was remarkable: a substantial presence of Streptococcus mutans, the bacterium known to cause tooth decay. Surprisingly, the enamel was still intact, indicating that this individual likely did not experience the severe dental decay that is often associated with poor oral health today.

The high levels of this cavity-causing bacterium were unexpected, as it was previously thought that ancient populations rarely encountered it due to their dietary practices, which were significantly lower in processed sugars and refined foods.

The Impact of Diet on Ancient Teeth

The findings shed light on the critical role of diet in the occurrence of dental cavities. In ancient times, humans lacked access to the refined sugars and carbohydrates that plague modern dental health. Their diets primarily consisted of whole foods, including fruits, vegetables, and wild grains, far less likely to encourage the proliferation of S. mutans compared to today’s processed diets.

By comparing the ancient dental microbiomes (the population of microorganisms in the mouth) with those of modern individuals, researchers observed significant differences. Prehistoric teeth showcased a far more diverse microbiome, resulting in fewer harmful bacteria that flourish on sugar and produce acids leading to tooth decay. The study indicates that the transition from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to agriculture—particularly with the introduction of grains like wheat and barley—led to increased carbohydrate consumption, which in turn saw a rise in cavities.

The Sugar Connection to Tooth Decay

Fast forward to the Industrial Revolution, when refined sugar consumption soared. This dietary shift adversely affected oral health, allowing S. mutans to flourish within the oral microbiome. This type of bacteria thrives in sugary conditions, metabolising sugars to produce acids that erode tooth enamel. The correlation between rising sugar intake and the increase in tooth decay over the last few centuries is quite striking.

Another surprising discovery from the research was the presence of Tannerella forsythia, a bacterium commonly associated with gum disease, in the ancient teeth. While still found in contemporary populations, its presence in prehistoric individuals suggests that their oral health was influenced by a different array of bacteria, which were not necessarily more harmful.

Examining the Shifting Microbiome

In prehistoric eras, humans boasted a more diverse oral microbiome, which offered protection against destructive bacterial overgrowth. However, the spread of agriculture and the rising consumption of refined sugars diminished this microbial diversity, paving the way for harmful bacteria like S. mutans to thrive.

This trend poses a concerning outlook for modern health, suggesting that the decline in microbial diversity might play a significant role in the burgeoning rates of oral diseases, including cavities and gum disease. Ongoing research is crucial to understanding how dietary and lifestyle changes over millennia have profoundly impacted our health.

Lessons for Modern Oral Health

Currently, our heavy reliance on processed foods, laden with sugars and refined carbohydrates, has led to a significant uptick in tooth decay and gum disease. Advances in modern medicine and dental care, featuring fluoride treatments and fillings, assist in managing these issues. Yet, the decline in bacterial diversity in our mouths remains a challenge for many, contributing to chronic dental concerns.

As research into the past unfolds, these findings underscore the vital role that our diet plays in shaping oral health. By reducing sugar intake and embracing a more natural, whole-food-based diet, we could potentially restore some balance to our oral microbiomes—possibly even reversing some negative impacts of contemporary eating habits.

In conclusion, the discovery of those ancient 4,000-year-old teeth and their bacterial makeup provides valuable insights into the changing dynamics between diet, bacterial diversity, and oral health. The evolution of our diet—from ancient grains to heavily refined sugars—has undeniably influenced the performance of our teeth and gums. Understanding this historical narrative not only deepens our appreciation for the significance of our dietary choices but also offers guidance for healthier practices moving forward.